Author(s): Connor Cuevo

Mentor(s): Amber Saxton, Office of Sustainability

AbstractThe University facilities team sets aside $100,000 per year in an independent organization known as the Patriot Green Fund. Run by a dedicated committee of faculty, staff and students, this fund identifies areas of infrastructure improvement on George Mason University campuses. It accepts, critiques, selects and finances creative, innovative, and eco-friendly solutions to these issues submitted primarily by students.

I and my team had the honor of being awarded university funding in the spring of 2021. We proposed a pilot program to assess the performance of a solar powered, self-compacting, high capacity trash receptacle to be installed outside of the Starbucks in Northern Neck hall.

I was approached almost two years ago in January 2020 by Sustainability Program Manager Amber Saxton, who notified me of several areas of potential campus improvement. I decided to explore alternative waste receptacles, due to the high costs and environmental impacts of providing liners for current trash bins and the frequently arising need to empty them, as well as rising complaints about litter and scavenging animals. After cursory research of the problem, an independent vendor known as BigBelly Solar seemed to provide a creative, sustainable and cost-effective solution.

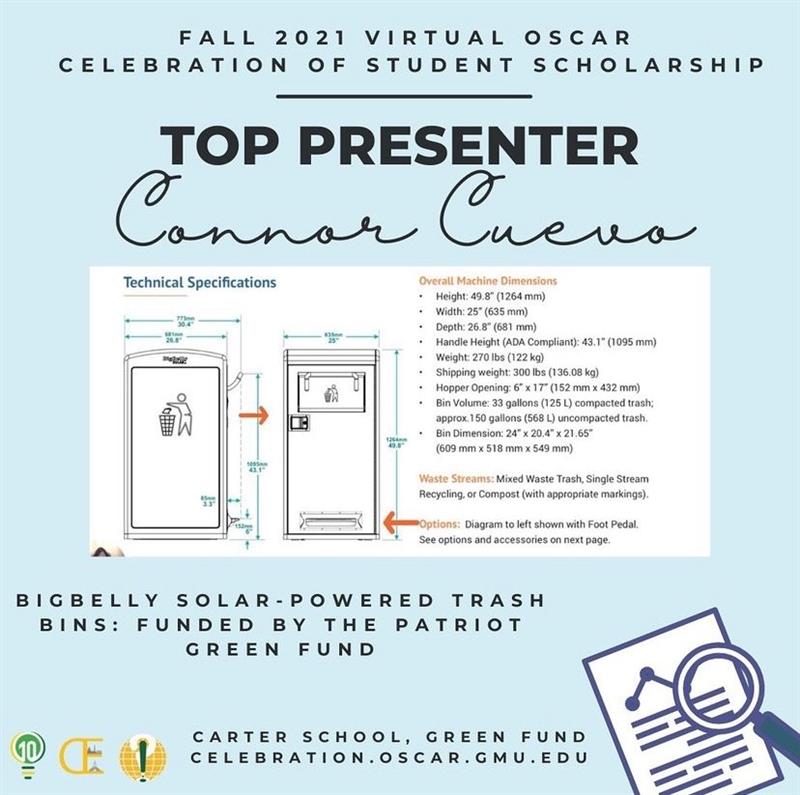

BigBelly units are large trash cans that compact the trash inside them. They are fully powered by renewable solar energy and hold nearly twice as much as standard campus trash bins, meaning less work and money saved for the university. A metal hatch seals the units to prevent access by pests and ensures that what goes in, stays in.

Amber introduced me to Colleen Regan, the Campus Efficiencies Assistant, who helped me conduct research and draft a proposal. Together we reached out to cities, universities and institutions all across the country who had previously purchased these units and asked all manner of questions about their specifications, cost, performance and maintenance. I also reached out to BigBelly directly for more information on their products. During this period, the three of us identified additional benefits of purchasing BigBelly units, such as a built-in ashtray, a foot-pedal to activate the hatch, and advertising space on the sides. Colleen and I determined that the University should purchase one trash bin and one recycling bin situated beside each other, with the future possibility of a compost receptacle or additional bins located elsewhere.

Amber, Colleen and I drafted a proposal. Before we began, I had the opportunity to meet with Sarah D’alexander, the Director of the Patriot Green Fund. Sarah explained to me that I would need to pass a preliminary round of examination by the committee to advance and become a finalist. My team and I worked hard to explain the problem and demonstrate our solution. The hardest part was crunching the numbers and determining that BigBelly would pay for itself in the span a of a few years. We submitted our proposal and patiently awaited a response.

However, before the committee could meet and assess our proposal, the covid-19 pandemic was gripping the US. Months of patiently waiting went by, before one day in July 2020, I received an email that the proposal had passed the initial stage and was a strong candidate for funding. Unfortunately, the pandemic was the cause of further delays both at Mason and across the globe, and it was not until the spring that we found the opportunity to make progress.

We got to work on the final proposal, amending our original draft and adding features such as a map to depict the waste bin’s location, and a chart which both detailed and provided a rationale for our expenditures. We explained each of our roles in the final application and demonstrated our commitment to see the project to completion. On February 5th, 2021, we submitted our final draft of the funding application.

Only a week or so had gone by, before I received an email from Sarah, informing me that the final application had been approved for funding. In class at the time, I nearly jumped for joy when I saw the notification. I was very proud of myself and my team. I couldn’t believe that I had won the first grant I had applied to! But I had to remind myself that my work was not done; I needed to follow through on what I had promised to deliver.

A few days later, I met with my team and with Sarah. We discussed the final three action items. First, we had to prove that our proposal was financially competitive, and this we accomplished by contacting two vendors who provide similar product and determining their prices. Second, since Bigbelly had no contract with George Mason University, we needed to provide one. Luckily, we located a similar contract with the vendor from an out of state organization which we were able to adapt to our own purposes. And lastly, we had to schedule several meetings with a university graphic design team to develop a durable, informative and visually appealing exterior for the Bigbelly unit.

Finally, in July 2021, the big day arrived. The facilities team led by Kevin Brim, head of campus recycling, installed the units right next to the Northern Neck Starbucks. Since then I have had the responsibility of continuing to monitor them; making sure that they are in efficient, working order, as well as checking for contamination. One area that needed troubleshooting was to determine the ideal level of waste and recycling the units can hold before they need to be emptied. Along with my team, I have participated in “waste audits” which involve digging through the trash and recycling to monitor contamination, as well as to assess the practicality and durability of the units.

But most of all, this is a pilot program, and if the units perform well, the university will consider expanding the project. BigBelly waste bins are a clear and visible symbol of Mason’s commitment to sustainability and innovation. The Patriot Green Fund is just one of many opportunities Patriots have to effect change on campus and beyond. Who knows what will be next?